Top Story

On 22 March, Professor Nathan Schiff of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics was presented with the ULI UK Academic Prize, awarded in partnership with The Journal of Economic Geography (JOEG) and Oxford University Press. Below are Schiff’s reflections on winning the award and a summary of his research.

It was quite an honour to receive the 2015 Urban Land Institute prize for my paper, “Cities and Product Variety: Evidence from Restaurants” (Journal of Economic Geography, November 2015). Prior to winning the prize I had only presented my work in front of academic economists. The ULI prize and ceremony has given me the opportunity to share my work with a larger audience of professionals in the planning and real estate community, most of whom don’t spend their days running regressions on restaurant counts, and can therefore offer insightful feedback from a different perspective. Below I provide a brief discussion of the main idea and findings from my paper.

One of the attractions of living in a big city is easy access to a large variety of local goods and services. But how much more variety do big cities offer? How do the specific varieties available differ in big and small cities? Why do bigger cities have greater variety? Does product variety simply increase proportionally to population?

Restaurants are uniquely suited to studying questions like these. They are local goods, they are easily categorized into different varieties by cuisine, and they are an important component of a city’s attractiveness.

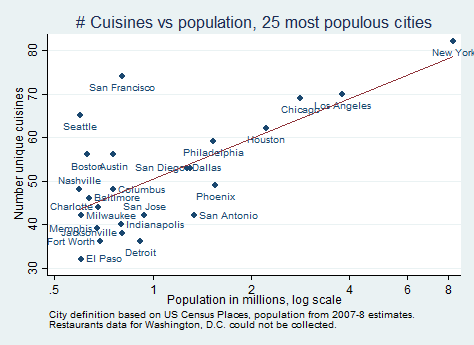

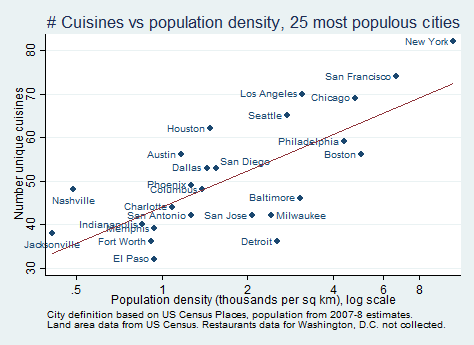

In the graphs below I plot the number of unique cuisines in a city (Italian, Thai, Venezuelan, etc.) against the population of the city (graph 1) and the population density of the city (graph 2) for the top 25 most populous cities in 2008, the year of my data. In the first graph we can see that population is clearly a good indicator of cuisine count but there are a fair number of cities with quite a bit more cuisines (San Francisco, Seattle, Boston) or quite a bit fewer cuisines (Indianapolis, Jacksonville, Detroit) than is predicted by city population. In the second graph we can see that the cuisine count of some cities is actually better predicted by population density (Phoenix and Philadelphia is a nice example). This suggests that a city’s geography, in addition to its population, may have an important role in explaining product variety.

In this paper I argue that cities increase their variety of restaurants by providing greater demand, which allows the entry of restaurants with rarer cuisines, or cuisines preferred by a smaller percentage of people. Bigger cities have greater demand both because they have larger populations and because they concentrate their population into a smaller space, meaning restaurants in denser cities have more potential consumers nearby.

This effect of population density can vary with the geographic size of the city so that the impact of both population and population density must be separately estimated. I use a unique dataset of over 127,000 restaurants across 726 cities in the year 2008 and estimate that a 1% increase in population increases a city’s cuisine count by 0.35-0.49%. Holding constant population, increasing a city’s population density by 1% increases a city’s cuisine count by an additional 0.16-0.21%. This could be thought of as fixing a city’s population but making everyone live closer together.

Since large cities have many times the population and density of small cities, these effects can be important in magnitude. Further, I find that cities with greater restaurant variety tend to have all of the cuisines found in cities with lesser variety but also have rarer cuisines. This type of hierarchical pattern means that the specific cuisines in a city can be predicted quite well by the simple count of cuisines.

All of these results hold after controlling for city demographics, such as ethnic diversity, income, education, and family size. I also perform analyses to show that the results are unlikely to be explained by confounding factors correlated with population and population density. The findings of this study not only confirm that bigger cities do indeed have much greater variety but that this variety itself is a direct consequence of city size and structure.

One of the ULI issue areas is promoting intelligent densification and urbanisation. In this paper I do not measure welfare, and thus cannot make any recommendations balancing the pros and cons of specific density policies. However, my results do suggest that policies which increase density may also increase consumption variety, providing an important benefit to local residents. Foodie city planners, take note.